When thinking of literary heritage manuscripts and objects, it’s too easy to focus purely on those items that were created or once owned by notable authors. The holdings of Blackburn Museum go some way to redress the balance, showing the importance of the collector in preserving our literary heritage.

When thinking of literary heritage manuscripts and objects, it’s too easy to focus purely on those items that were created or once owned by notable authors. The holdings of Blackburn Museum go some way to redress the balance, showing the importance of the collector in preserving our literary heritage.

Blackburn is not a town that is renowned for its cultural impact. In the 18th century, it became known as a key town in the burgeoning textile industry, one of many North West towns that was to benefit from the expanding cotton industry over the course of almost two centuries. Today, all that is left of this boom in Blackburn are the grand buildings, such as the town hall or the refurbished Waterloo Pavilions. The famous Thwaites Brewery, a feature of the town since 1807, is the last remaining business from Blackburn’s industrial past. The collection of R.E. Hart at the Blackburn Museum is another sign of the town’s affluent history. Continue reading

The places in which writers lived and worked become inextricably linked with their art within the public consciousness. Would the works of Wordsworth have captured the imaginations of such a large audience, and be held as treasures of the nation’s culture, if it was not for his poetic rendering of the Lake District? Does it matter that Shakespeare’s true home was outside of the London society he was observing and satirising? How would Dickens’s work be different if he had chosen a rural life rather than his metropolitan existence? These are perhaps unanswerable questions, but the notion that place has an artistic power is a persistent one.

The places in which writers lived and worked become inextricably linked with their art within the public consciousness. Would the works of Wordsworth have captured the imaginations of such a large audience, and be held as treasures of the nation’s culture, if it was not for his poetic rendering of the Lake District? Does it matter that Shakespeare’s true home was outside of the London society he was observing and satirising? How would Dickens’s work be different if he had chosen a rural life rather than his metropolitan existence? These are perhaps unanswerable questions, but the notion that place has an artistic power is a persistent one. ![Bronte Parsonage Museum, Haworth bronte-parsonage-museum[1]](https://englitheritage.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/bronte-parsonage-museum1.jpg?w=300&h=225) The English Literary Heritage project has been conducting a survey for the past few months, and it is beginning to yield some interesting insight. What visitors to museums, archives and literary houses are telling us partly builds upon expectations but also reveals different priorities for both individuals and groups.

The English Literary Heritage project has been conducting a survey for the past few months, and it is beginning to yield some interesting insight. What visitors to museums, archives and literary houses are telling us partly builds upon expectations but also reveals different priorities for both individuals and groups. While web-based applications such as ‘Turning the Pages’ offer a good opportunity to access precious and rare manuscripts outside of formal, controlled environments, they do not necessarily provide a curated experience. In essence, they present single exhibits, individual manuscripts which do not have a narrative or interpretative shape. Yet, there is a growing trend in applications for tablet computers and other mobile devices, software that allows the user to explore a virtual exhibition of manuscripts and other material alongside original texts. These apps can be focused and curated, presenting an interpretative view of an author’s work and the archival materials surrounding its creation.

While web-based applications such as ‘Turning the Pages’ offer a good opportunity to access precious and rare manuscripts outside of formal, controlled environments, they do not necessarily provide a curated experience. In essence, they present single exhibits, individual manuscripts which do not have a narrative or interpretative shape. Yet, there is a growing trend in applications for tablet computers and other mobile devices, software that allows the user to explore a virtual exhibition of manuscripts and other material alongside original texts. These apps can be focused and curated, presenting an interpretative view of an author’s work and the archival materials surrounding its creation.

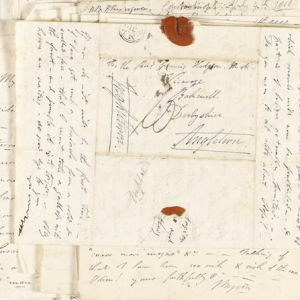

Out of all the manuscripts contained within a literary archive, authors’ letters perhaps promise the most naked insight into the mind of the artist. Quite often, these letters are intimate, confessional, the authors’ naked voices so different to published material or interviews where, knowing their words will be seen by a larger audience, they are on their best behaviour. This appearance of intimacy can be intoxicating for the researcher. It can often feel like eavesdropping on a private conversation, discovering an author’s unabridged opinions on everything from writing, to book, to political insights, as well as the tantalising pieces of gossipy trivia that reveal the author’s life, loves and more. But literary letters are much more complex documents than this sense of guard-down intimacy indicates. It is well known that the Romantic Poets would correspond with each other frequently, and many of these letter have become famous in their own right:

Out of all the manuscripts contained within a literary archive, authors’ letters perhaps promise the most naked insight into the mind of the artist. Quite often, these letters are intimate, confessional, the authors’ naked voices so different to published material or interviews where, knowing their words will be seen by a larger audience, they are on their best behaviour. This appearance of intimacy can be intoxicating for the researcher. It can often feel like eavesdropping on a private conversation, discovering an author’s unabridged opinions on everything from writing, to book, to political insights, as well as the tantalising pieces of gossipy trivia that reveal the author’s life, loves and more. But literary letters are much more complex documents than this sense of guard-down intimacy indicates. It is well known that the Romantic Poets would correspond with each other frequently, and many of these letter have become famous in their own right:

The study of manuscripts reveals many things about an author’s work, but the revisions the author made on the rough draft can be especially telling. William Wordsworth took the art of revision very seriously, spending over 50 years perfecting his longest poem, The Prelude (1799-1850), fragments of which can be seen in letters, notebooks and other manuscripts in the holdings of the Wordsworth Trust. Revisions and omission in later drafts reveal Wordsworth’s changing emphases and political views.

The study of manuscripts reveals many things about an author’s work, but the revisions the author made on the rough draft can be especially telling. William Wordsworth took the art of revision very seriously, spending over 50 years perfecting his longest poem, The Prelude (1799-1850), fragments of which can be seen in letters, notebooks and other manuscripts in the holdings of the Wordsworth Trust. Revisions and omission in later drafts reveal Wordsworth’s changing emphases and political views.  A literary archive should not be viewed as a full and unadulterated view into the mind of the author. The act of assembling the archive, choosing what exactly is put into the archive, creates only a fractured, often stage-directed, image of authors and their work. A good example of this is the David Foster Wallace archive, assembled by Karen Green and Bonnie Nadell (his widow and agent respectively). The archive, as bought by the Harry Ransom Center, is carefully presented: there is little personal correspondence, no journals or other documents relating to Wallace’s intimate and private life. The archive concentrates on the work: typescripts, notebooks, rough drafts, the occasional scribbling of nascent ideas. Similarly, only items from Wallace’s library that he annotated were put into the archive, meaning only a slight fragment of Wallace’s literary life can be determined.

A literary archive should not be viewed as a full and unadulterated view into the mind of the author. The act of assembling the archive, choosing what exactly is put into the archive, creates only a fractured, often stage-directed, image of authors and their work. A good example of this is the David Foster Wallace archive, assembled by Karen Green and Bonnie Nadell (his widow and agent respectively). The archive, as bought by the Harry Ransom Center, is carefully presented: there is little personal correspondence, no journals or other documents relating to Wallace’s intimate and private life. The archive concentrates on the work: typescripts, notebooks, rough drafts, the occasional scribbling of nascent ideas. Similarly, only items from Wallace’s library that he annotated were put into the archive, meaning only a slight fragment of Wallace’s literary life can be determined.