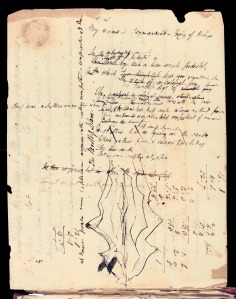

Literary manuscripts often lend themselves more to quiet and considered study than being displayed in a public space. Reading, for most people, is a solitary and thoughtful activity, usually undertaken in a comfortable chair, not standing in a public exhibition space jostling with other visitors. Manuscripts, unlike paintings or historical objects, are not just physical artefacts, they contain a plenitude of words and meanings that can be an overwhelming prospect for the museum visitor. As Jeff Cowton, curator at the Wordsworth Trust, writes, ‘To the initiated, a row of a favourite author’s manuscripts is something to dream of; to the uninitiated, such a display may fail to inspire even a wish to learn more’. To make those uninitiated connect with manuscripts and leave enlightened is the chief challenge of the literary exhibition.

Literary manuscripts often lend themselves more to quiet and considered study than being displayed in a public space. Reading, for most people, is a solitary and thoughtful activity, usually undertaken in a comfortable chair, not standing in a public exhibition space jostling with other visitors. Manuscripts, unlike paintings or historical objects, are not just physical artefacts, they contain a plenitude of words and meanings that can be an overwhelming prospect for the museum visitor. As Jeff Cowton, curator at the Wordsworth Trust, writes, ‘To the initiated, a row of a favourite author’s manuscripts is something to dream of; to the uninitiated, such a display may fail to inspire even a wish to learn more’. To make those uninitiated connect with manuscripts and leave enlightened is the chief challenge of the literary exhibition.

Another challenge is how to offer supplementary material, notes on the context of the manuscript, transcripts, hints at possible interpretations and the like, without adding yet more off-putting blocks of reading. These cards, designed to offer visitors access to what is being displayed, can obscure the physical manuscript by being given too much priority in the exhibition space. Important though it is to offer visitors the story behind the exhibit, there is a danger of the physical manuscript receding out of view as people concentrate on the supplementary information.

One barrier to visitors’ understanding of the manuscript is the necessity of keeping it behind glass. More often than not, the manuscripts on display are extremely valuable and delicate, so they are contained within cases, meaning only one opening can be displayed. There is a temptation to let visitors see the most visually arresting parts of the manuscript, such as illustrations or title pages, but these don’t necessarily best describe the importance of the words contained within.

One barrier to visitors’ understanding of the manuscript is the necessity of keeping it behind glass. More often than not, the manuscripts on display are extremely valuable and delicate, so they are contained within cases, meaning only one opening can be displayed. There is a temptation to let visitors see the most visually arresting parts of the manuscript, such as illustrations or title pages, but these don’t necessarily best describe the importance of the words contained within.

These are some of the challenges facing the English Literary Heritage project as we attempt to research the best ways to display manuscripts and other literary objects in a museum or gallery. The initial research has focussed on several important aspects.

Firstly, there has been an attempt to chart people’s experiences when they visit an exhibition. Jan Packer describes four different types of experience that someone has when looking at an exhibit: object experiences, with a focus on something outside the individual such as rare and valuable objects; cognitive experiences, which focus on interpretative or intellectual aspects, including gaining information or an enriched understanding; introspective experiences, which focus on the private feeling of the individual such as imagining, reflecting and reminiscing; social experiences, which focus on interaction with other visitors or museum staff. Part of the English Literary Heritage project is to determine whether these different experiences can be both monitored and inspired by using technology in the literary museum.

These experiences can be measured in a number of ways, from exit interviews or questionnaires for museum visitors, or more sophisticated techniques. Sue Allen, writing about visitor analysis for an exhibition on frogs at The Exploratorium science museum in San Francisco, offers the example of remotely recording the conversations of a select group of willing visitors as they look at the exhibition. Allen’s survey, conducted between 1999 and 2000, recorded conversations of visitors with radio microphones and charted the visitors’ positions in the exhibition by covert surveillance. These tactics yielded results for the specific exhibition, but could be adapted to learn about visitor expectations of, and reactions to, a literary exhibition. Technologically, this sort of surveillance would now be much easier to achieve, perhaps using GPS instead of a human ‘tracker’ and smaller digital microphones.

These experiences can be measured in a number of ways, from exit interviews or questionnaires for museum visitors, or more sophisticated techniques. Sue Allen, writing about visitor analysis for an exhibition on frogs at The Exploratorium science museum in San Francisco, offers the example of remotely recording the conversations of a select group of willing visitors as they look at the exhibition. Allen’s survey, conducted between 1999 and 2000, recorded conversations of visitors with radio microphones and charted the visitors’ positions in the exhibition by covert surveillance. These tactics yielded results for the specific exhibition, but could be adapted to learn about visitor expectations of, and reactions to, a literary exhibition. Technologically, this sort of surveillance would now be much easier to achieve, perhaps using GPS instead of a human ‘tracker’ and smaller digital microphones.

Technology can also be used to bring life to the manuscripts on display. The British Library’s ‘Turning the Pages’, an app that digitally recreates the manuscripts so that the user can virtually turn pages and examine every word, goes some way to defeat the glass boundary between artefact and visitor. The terminals in the British Library’s treasures room also give some additional material, such as transcripts and contextual information.

Another way of overcoming the challenges of exhibiting manuscripts could lie in the use of RFIDs (Radio Frequency Identification). These are small chips that can be placed in any object (cards, hand-held clickers etc.) which will be able to interact with museum exhibits to present further information online that the user can access at their discretion (the London Underground’s Oyster Card system uses this type of RFID). Sherry Hsi details how RFIDs can enhance the museum experience for visitors, writing, ‘Using an RFID package such as an electronic watch, a card, a yo-yo, or a remote clicker, a visitor could bookmark the exhibit he/she is visiting (which sends his/her unique ID to the network via an RFID transceiver mounted on the exhibit)’. This could lead to a unique webpage that collates the information that the user is interested in, making much of the museum’s reading material available for reflection at a later time. A system such as this could provide a solution to the text-heavy nature of literary exhibitions.

Another way of overcoming the challenges of exhibiting manuscripts could lie in the use of RFIDs (Radio Frequency Identification). These are small chips that can be placed in any object (cards, hand-held clickers etc.) which will be able to interact with museum exhibits to present further information online that the user can access at their discretion (the London Underground’s Oyster Card system uses this type of RFID). Sherry Hsi details how RFIDs can enhance the museum experience for visitors, writing, ‘Using an RFID package such as an electronic watch, a card, a yo-yo, or a remote clicker, a visitor could bookmark the exhibit he/she is visiting (which sends his/her unique ID to the network via an RFID transceiver mounted on the exhibit)’. This could lead to a unique webpage that collates the information that the user is interested in, making much of the museum’s reading material available for reflection at a later time. A system such as this could provide a solution to the text-heavy nature of literary exhibitions.

These are just two ways technology could be used to overcome many of the challenges of exhibiting literary manuscripts and objects in a museum environment. Part of the English Literary Heritage project’s remit is to assess how successful these existing digital displays are in allowing the user to connect with the manuscript. These assessments will feature in future posts on this blog.